Survey on Marriage Culture in India

Disclaimer: This survey is not an accurate estimation of the culture of marriage in India due to limitations of the manner in which the study was conducted as well as the respondent base. There are bound to be variations across different societal demographics and hence the conclusions we arrived at should be seen in this relative light. Also we advise that generalizations not be made off this survey , it is just to give readers a peek into certain findings we came across.

Introduction

In 1942, renowned Indian sociologist and social anthropologist M.N Srinivas published his book, ‘Marriage and family in Mysore’. Srinivas undertook field studies in various villages and regions in Mysore and penned down his findings of the same. As a matter of fact, one of the observations he made was that ''romantic love as a basis of marriage is still not very deep or widely spread in the family mores of India today”. Surprisingly even 6 decades later this observation still occupies a significant enough space in Indian society.

Even with changing demographics and advances in terms of declining fertility levels, rising education for both boys and girls, and growing integration into the global economy, South Asia in general and India, in particular, is considered an outlier in terms of nuptial transition because of the persistence of parent arranged marriage systems and low divorce rates (Jones 2010) and low age at marriage for women (Andrist, Banerji and Desai 2013).

Continued loyalty of the individual to the family of orientation and kin group is the most cherished ideal in the Indian family system and forms the principle underlying the phenomenon of arranged marriage. Last month Netflix came out with Indian Matchmaking, an 8 episode docuseries that focussed on Sima Taparia, a marriage consultant engaged in finding appropriate matches for her upper-class clientele. The show revolved not just around Taparia, but also navigated around the culture of arranged marriage and matchmaking in India, depicting the interplay of family, society, belief systems and culture in the process of finding alliances. Read about our thoughts on it here.

This got us a little invested (in both IMM and the culture of arranged marriage in India). So we dug in a little deeper and looked at some specific perspectives on the same. We carried out a micro survey to assess the culture of matchmaking and marriage in India, specifically that of arranged marriages, its prevalence across Indian society, and the gendered impacts of the same.

Who did we survey?

The survey had 319 respondents, with 63.3% falling in the age group of 22-30, 20.4 % between 19-21 and 13.5 between 31- 40 years of age.

85% of the participants identified as female, 13.5% as male, and 2 respondents belonged to the LGBTQ+ community.

What was their marital status?

15% of the total participants were married with 64.6% of participants having love marriages while 35.4% said that they had arranged marriages.

We categorized them as two sets of respondents for the next part of our analysis.

Observations across the Two Categories

The median marriageable age for both arranged and love marriage was around 26. However, in the case of love marriages, the most common age for marriage did range between 24- 26 years of age while for arranged marriage it sharply stood at 26.

With love marriages, respondents also said that once their families were aware of their relationship, they did face a certain amount of pressure to be married as soon as possible (one factor that could explain the difference in age between both modes of marriage).

87% of respondents who had love marriages said that there had been a precedence of the same in their families. Often previous incidents of such forms of marriage taking place, provide a more conducive environment for the same.

67.7% of respondents said that their families were accepting of their spousal decision and about 10.5% claimed that their families took time to come to terms with it.

Over half of the respondents in both arranged marriages and love marriages reported family pressure to get married. In the case of arranged marriage, some said that though subtle, the pressure still existed while others said that the process was pressurizing because often things didn’t seem to be working out.

When asked about their family’s take on love marriage 41.2% of respondents said that their families were against the practice and even when accepting of it, certain conditions were still deterministic prerequisites like that of education and religion.

On Religion and Religious Practices

When it came to the matter of family acceptance of one’s romantic partners, even though 48% of respondents said that their families would be accepting of the same, 11% of respondents specified that similarity of caste and religion were strict preconditions to the acceptance. A few responses even indicated that relationships would only be accepted if there was a firm assurance that it would end in marriage.

Overall the effect of religion guiding patterns of behavior was also evident in the fact that 53% of total respondents said that their family was likely to follow activities mandated by religious beliefs and hence this might explain why the conditions for the acceptance of one’s romantic partner was influenced by factors such as caste and religion.

Among respondents who had love marriages, around 52% of marriages were either inter-caste or inter-religious, with inter-caste accounting for a 39% share. Many respondents who deviated from the societal norm of arranged marriages said that often their extended families were unaccepting of their marriage even in cases where their parents had no objections. Many respondents also noted that there was strict conformity in terms of weddings taking place according to religious traditions.

With inter-caste and inter-religious marriages, weddings were often stressful because of the differences in religious traditions and families being less accommodating of the same.

Not surprisingly, when it came to arranged marriages all respondents said that their spouses belonged to the same religion as them.

Around 47% of respondents who had arranged marriages, believed that on a scale of 1-,5 religion and education were the two most important factors influencing marriages (other factors were income level and ethnicity).

These results were mirrored by non-married respondents who said that there was a strong influence that religion and education played in marriages within their families.

On Income and Marriage

In the case of love marriage, most respondents said that both partners fell in the same income bracket however the percentage that said no was not drastically lower. However, in the case of arranged marriage, there was a sharp difference, where 68.8% of respondents said that they did not belong to the same income bracket as their partner.

Data for respondents belonging to the ‘love-marriage’ category.

Data for respondents belonging to the ‘arranged-marriage’ category.

On Occupation and Marriage

The impact that occupation has upon marital alliances was also studied in a qualitative manner through the survey. Some respondents said that they preferred partners in the same line of work so that it would be easier to navigate around a work-life balance.

Occupational timings particularly night shifts were seen as problematic by potential alliances as well as in-laws. This was observed across all genders.

In specific instances, the choice of the workplace was also looked upon in a negative light by the family of the prospective alliance. One female respondent said that her job at a media house was not seen as favorable. Another respondent noted that there was a demand made by her in-laws to pursue her PG in a particular profession as it fell in line with the family-run business. Other observed responses involved demands placed upon individuals to leave their corporate careers and pursue jobs such as teaching while some were told that post-marriage further studies would not be encouraged.

What was the process of finding alliances in an arranged marriage?

Around 77% of respondents used matrimonial sites while around 65 percent used the help of family members(the percentage includes those who used sites and family members).

As already established the importance attributed to mediators in the process of matchmaking (whether a family member or a hired consultant) is integral to forming marital alliances and greater importance is often given to the opinion of the said mediator especially that of a family member. In line with this around 47% of respondents also claimed that their families did express dissatisfaction when respondents did not agree with their prospective marital proposals.

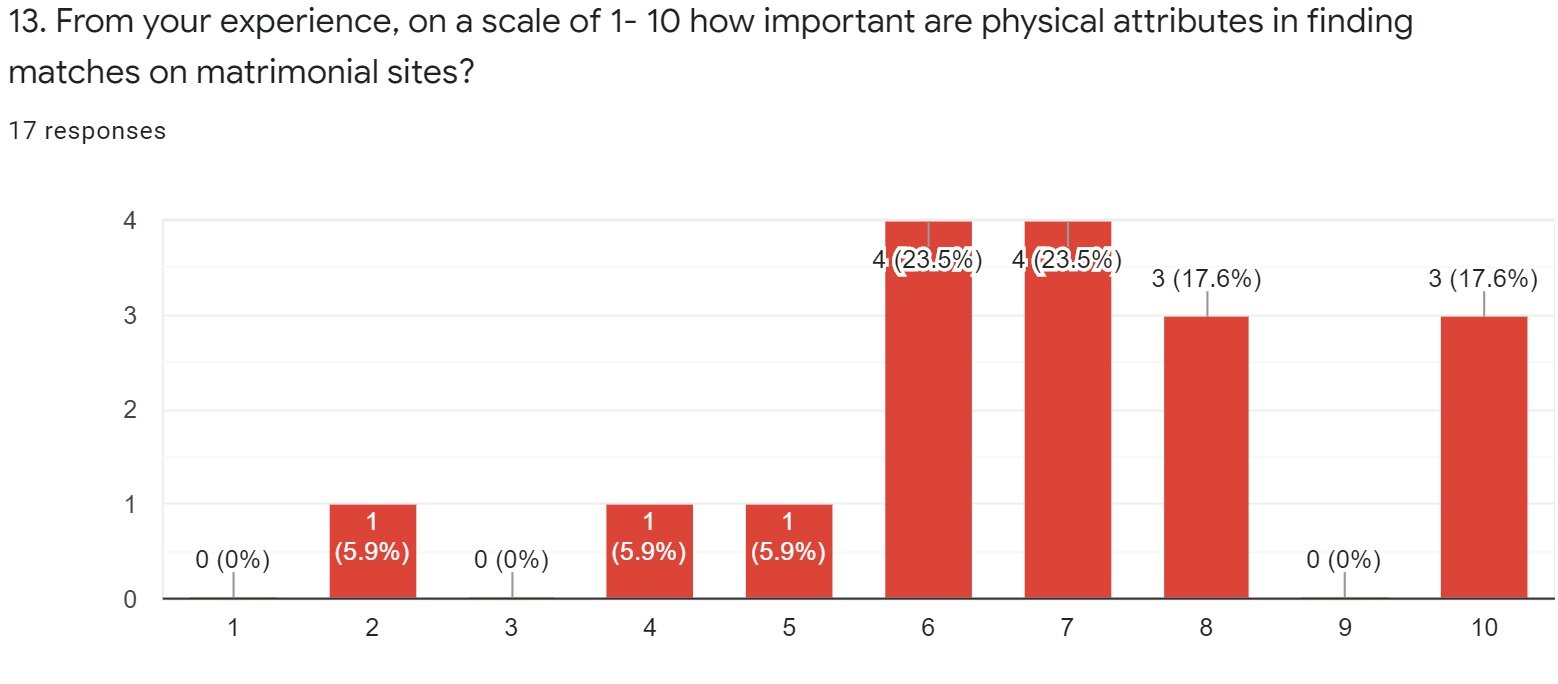

When asked to rank the importance of physical attributes, well over 70% of respondents believed that the impact such attributes had on the marital alliance was over the average mark. Around 17.6% of respondents ranked its impact as a 10 on the Likert scale.

This finding has supportive evidence in previous research carried out. A 2009 study carried out by Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak, and Jeanne Lafortune, observed in their sample of highly educated females and males, fewer than 25 percent of matched brides were working after marriage. Marriage was seen as a heavy economic investment to be managed by parents rather than prospective spouses. (Duflo, Banerjee, Ghatak, & Lafortune, 2013). The study which looked at matrimonial adverts and sites also indicated a strong preference for in-caste matches in both men and women.

Although education was seen as important, physical attributes continue to strongly influence marriage outcomes with the call back rate of a fair woman without education is much higher than a dark-skinned woman with a degree.

Qualitative findings

The survey also tried to qualitatively assess if respondents who had love marriages, would trust their parents to find them a spouse.

When asked if they would want their parents to carry out the process of finding a partner:

Most responses were centered around the fact that there is/was an asymmetry in the kind of factors that the respondent believed would make a good spouse as well as belief systems, values, and lifestyle choices versus those that were considered ideal by their parents. Although there is a concession made by many that their parents have their best interests in mind, most respondents said that they did not want their parents to help them find a spousal match. With those who said yes, they believed that the final decision was always independent of what their family wanted but they did trust their families well enough to find them a suitable match.

When asked if they had heard terms such as adjustment and compromise:

A huge majority of respondents replied in the affirmative saying that the idea of compromise and adjustment was also heavily gendered in the sense that it affected most womxn.

Even with supportive close family members, a respondent who had a full-time career said she faced judgment from others in society for not cooking for her family. Other issues brought up by female respondents involved compulsorily living with in-laws/joint families, wearing traditional clothing, mandatory knowledge of knowing how to cook and carry out household tasks, etc.

The idea of compromise as perceived in love marriage is seen as something that people are expected to deal with since it was their decision to marry a partner if their choosing , to begin with and hence the idea of complaining and not adjusting is not tolerated.

When asked about how media impacts the perception of marriages:

A huge chunk of respondents said that the media often dictates what is supposed to be acceptable and unacceptable norms in relationships, usually based on society's expectations. It also perpetuates harmful and stereotypical gender roles.

The dynamic between partners within the space of marriage is also problematic since it often ‘normalizes toxic behavior such as women seeking ‘permission’ from their husband and a loss of self-identity,’ where that of the husbands, ‘head of the house’ takes precedence.

Media portrayal also looks at marriage as a goal that everyone in society should necessarily aspire to. ‘The idea of being complete only with a ‘better half’ is propagated by media culture. Ideas of elaborate, expensive ‘dream’ marriages, lack of representation of diversity, or minorities are also problems that many pointed out.’ Even in media that seemingly promotes progressive, choice-based norms related to marriage culture, the deep-rooted conservative approach of most Indian households means that they laud and appreciate such forms of media but also advocate for it to be ‘kept out of ‘our’ house.’

Since it often ‘normalizes toxic behavior such as women seeking ‘permission’ from their husband and a loss of self-identity,’ where that of the husbands, ‘head of the house’ takes precedence.

Media portrayal also looks at marriage as a goal that everyone in society should necessarily aspire to.

Giri Raj Gupta in his paper on ‘Love, Arranged Marriage and the Indian Social Structure’, highlights a key element that I believe one can keep coming back to. He says that as long as the social system does not develop values that promote individualism, economic security outside the family system as well as a value system that does not prioritize the joint family, then the phenomenon of arranged marriage will continue to prevail. Even the forces of modernization that support romantic love would not truly be absolute in the sense that all the moral and material support for romantic forms would still come from the extended/joint family.

References

Duflo, E., Banerjee, A., Ghatak , M., & Lafortune, J. (2013). Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 33-72.

Gupta, G. R. (1976). Love, Arranged Marriage, and the Indian Social Structure. Journal of Comparative Family Studies

Lisa Jacob

Lisa is a cheesecake enthusiast who looses hair ties by the day, enjoys long runs and hopes to one day finish reading all the many journal articles she has downloaded on her desktop.